Monsoon rains have caused devastating floods in Pakistan, leaving millions homeless, destroying buildings, bridges and roads and leaving vast swathes of the country under water.

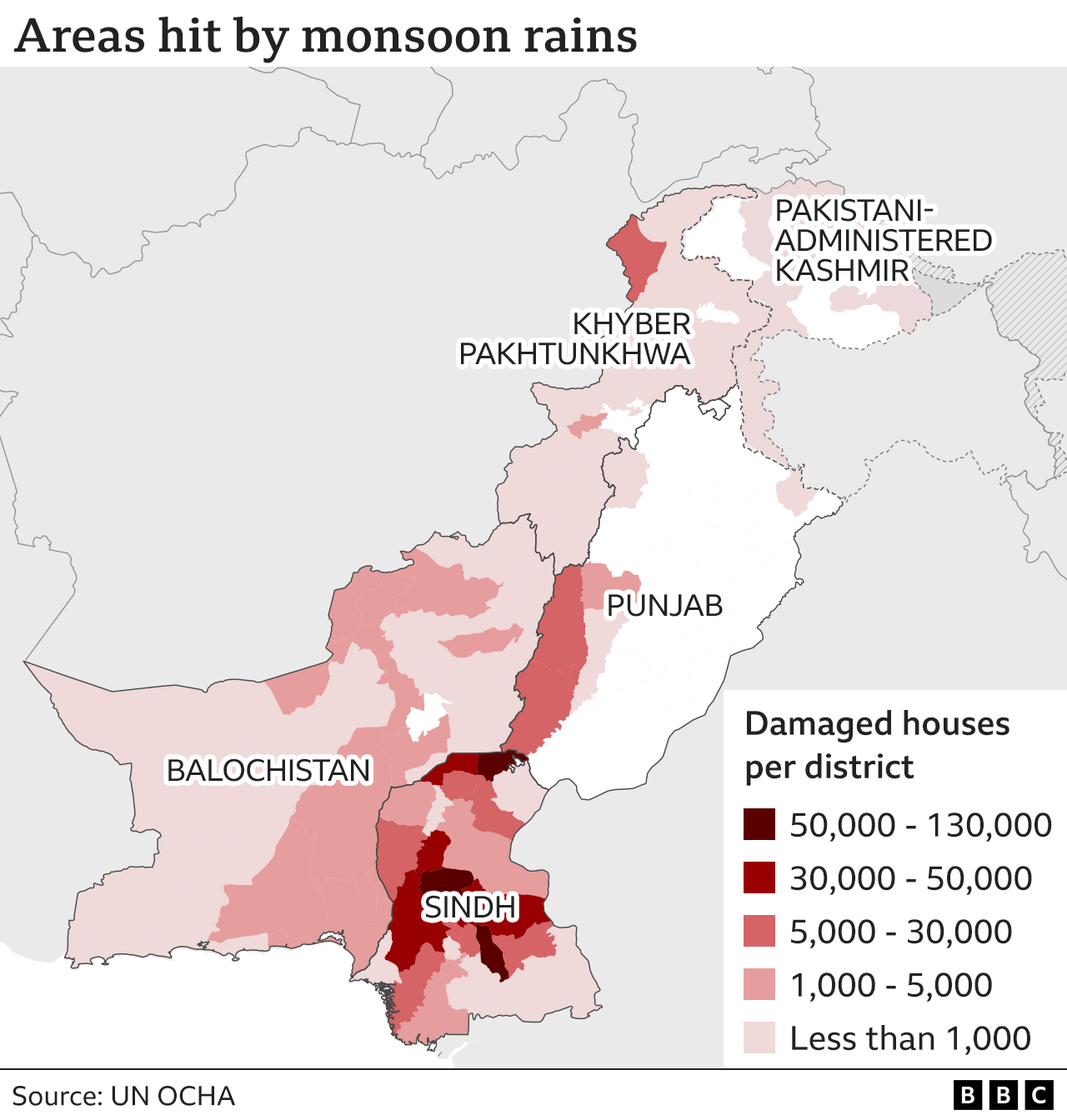

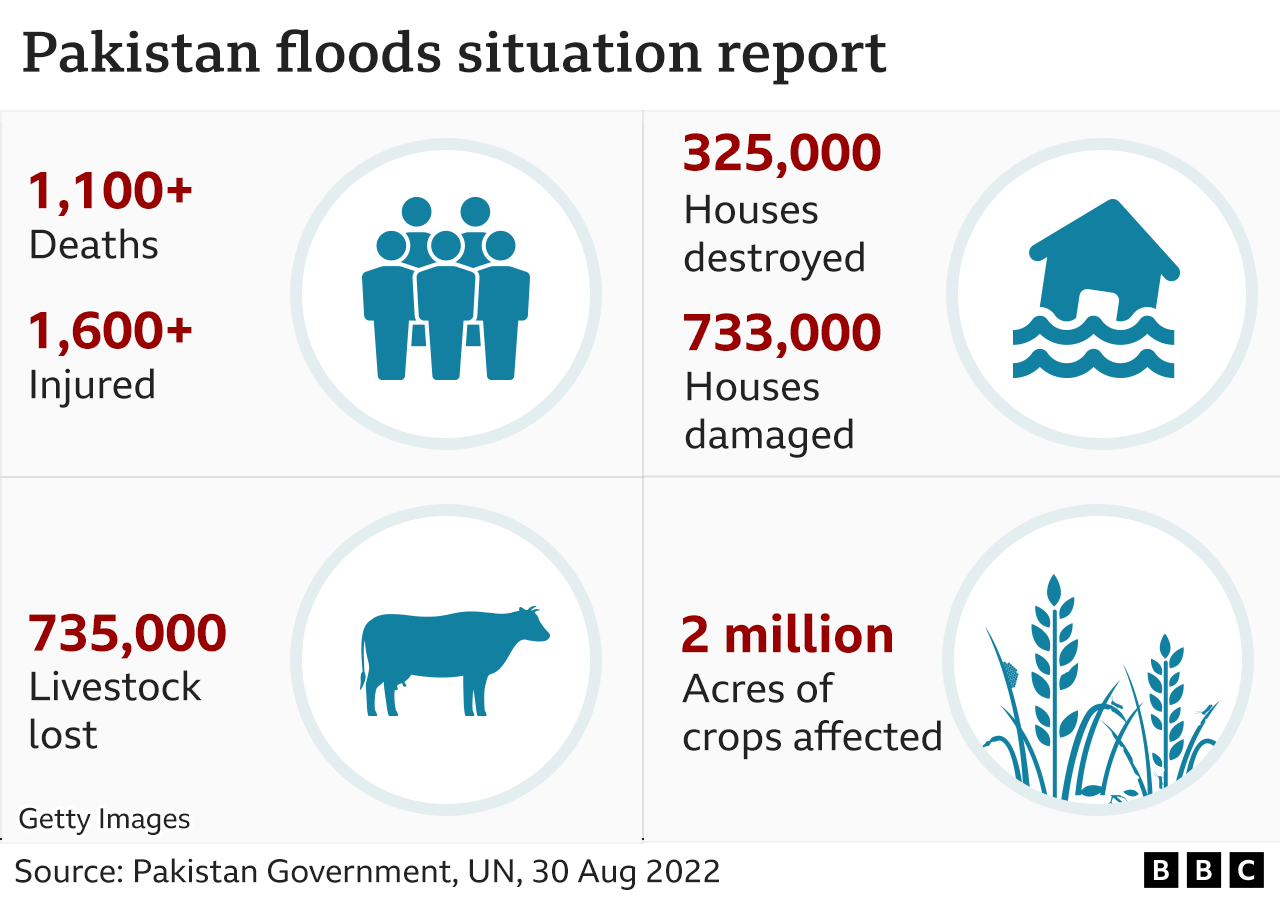

Flash floods and landslides along the Indus and Kabul rivers have left more than 1,000 dead and 1,600 injured – with the southern districts of Balochistan and Sindh worst-affected.

Monsoon rains have caused devastating floods in Pakistan, leaving millions homeless, destroying buildings, bridges and roads and leaving vast swathes of the country under water.

Flash floods and landslides along the Indus and Kabul rivers have left more than 1,000 dead and 1,600 injured – with the southern districts of Balochistan and Sindh worst-affected.

Mountainous regions in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa have also been badly hit.

The climate change minister says more than a third of the country has been completely submerged by the heaviest recorded monsoon rains in a decade.

The Indus River which flows through Sindh and Balochistan is fed by mountain tributaries in the north of the country, many of which have burst their banks following record rains and melting glaciers.

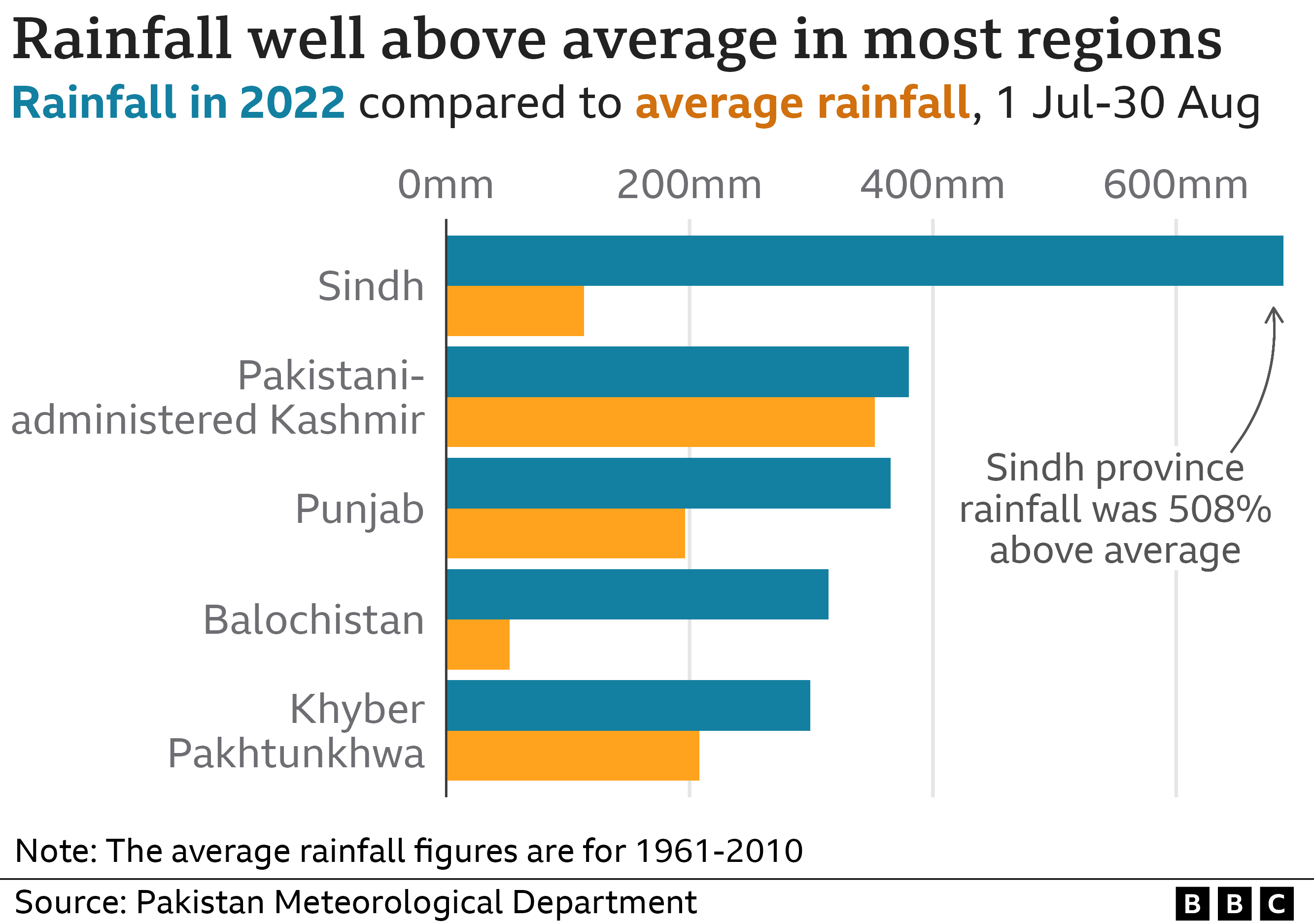

The UN’s World Meteorological Organization said Pakistan and north-west India have had an intense monsoon season this year – with one site in Sindh reporting 1,288 millimetres of rain so far in August, compared with the monthly average of 46mm.

There are echoes of the devastating floods of 2010 – the deadliest in Pakistan’s history – which left more than 2,000 people dead.

Damage to thousands of kilometres of roads and dozens of bridges this season has hampered access to flood-hit areas.

People have been forced to take shelter on higher ground wherever they can – on elevated roads and railway tracks, many accompanied by surviving livestock. Others have sought shelter in camps run by aid agencies.

Government and army helicopters have been called in to rescue stranded villagers and tourists – as well as deliver aid.

The UN estimates that around 33 million Pakistanis – one in seven people – have been affected by the flooding, with more than 500,000 houses destroyed or damaged.

Raging flood waters have also swept away 700,000 head of livestock and damaged more than 3.6 million acres of crops – wiping out cotton, wheat, vegetable and fruit harvests.

https://flo.uri.sh/visualisation/11046022/embed?auto=1

“Millions are homeless, schools and health facilities have been destroyed, livelihoods are shattered, critical infrastructure wiped out, and people’s hopes and dreams have washed away,” UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres said on Tuesday.

He was speaking at the launch of an appeal to raise £137m to help provide 5.2 million people with food, water, sanitation, emergency education, protection and health support.

Is climate change to blame?

Pakistan has been left reeling from a double whammy of climate-related disasters this year. Heatwaves in March and April saw temperatures soar above 49C, while surging floods have now washed away almost everything in their path, leaving tens of millions in need of aid.

Scientists were quick to attribute the heat to climate change driven by humans, and the shadow of human-induced global warming clearly hangs over this new disaster.

This year the country has been hit by the largest amount of rainfall in three decades – and it’s an irrefutable scientific fact of an overheating world that a warmer atmosphere holds more water, making downpours far more intense.

Pakistan also has the largest number of glaciers outside of the polar regions and higher temperatures have led to more water tumbling down from melting ice in the Himalayas.

But there are other factors at play here that have contributed to the scale of devastation. These include long-term deforestation and government failures to make adaptive changes since the last major flooding event in 2010.

There’s no doubt the world will help out in the immediate aftermath of this disaster – but the bigger question is: Will the richer world pay to prevent a repetition?

The Pakistani government estimates it will need $7-14bn (£6-12bn) per year, every year until 2050, for adaptation and to build climate resilient infrastructure.

Developing countries argue that Europe and the US should cough up the cash because of their historic emissions of warming gases.

Diplomats failed to solve this question at COP26 – and it will loom large as countries gather in Egypt for COP27 in two months’ time.