Countries will have to increase their carbon-cutting ambitions five fold if the world is to avoid warming by more than 1.5C, the UN says.

The annual emissions gap report shows that even if all current promises are met, the world will warm by more than double that amount by 2100.

Richer countries have failed to cut emissions quickly enough, the authors say.

Fifteen of the 20 wealthiest nations have no timeline for a net zero target.

Hot on the heels of the World Meteorological Organization’s report on greenhouse gas concentrations, the UN Environment Programme (Unep) has published its regular snapshot of how the world is doing in cutting levels of these pollutants.

The emissions gap report looks at the difference between how much carbon needs to be cut to avoid dangerous warming – and where we are likely to end up with the promises that countries have currently committed to, in the Paris climate agreement.

The UN assessment is fairly blunt. “The summary findings are bleak,” it says. “Countries collectively failed to stop the growth in global greenhouse gas emissions, meaning that deeper and faster cuts are now required.”

The report says that emissions have gone up by 1.5% per year in the last decade. In 2018, the total reached 55 gigatonnes of CO2 equivalent. This is putting the Earth on course to experience a temperature rise of 3.2C by the end of this century.

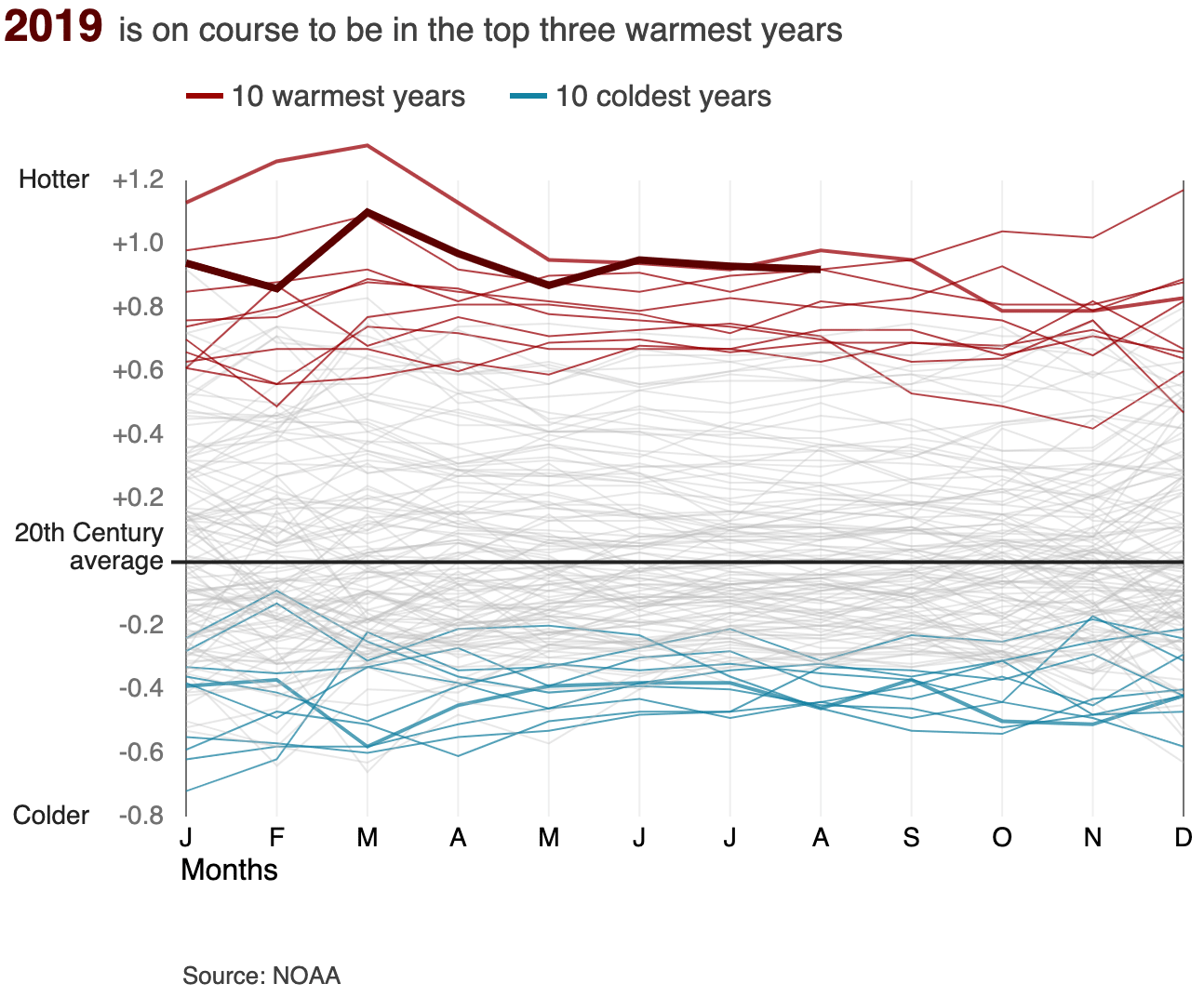

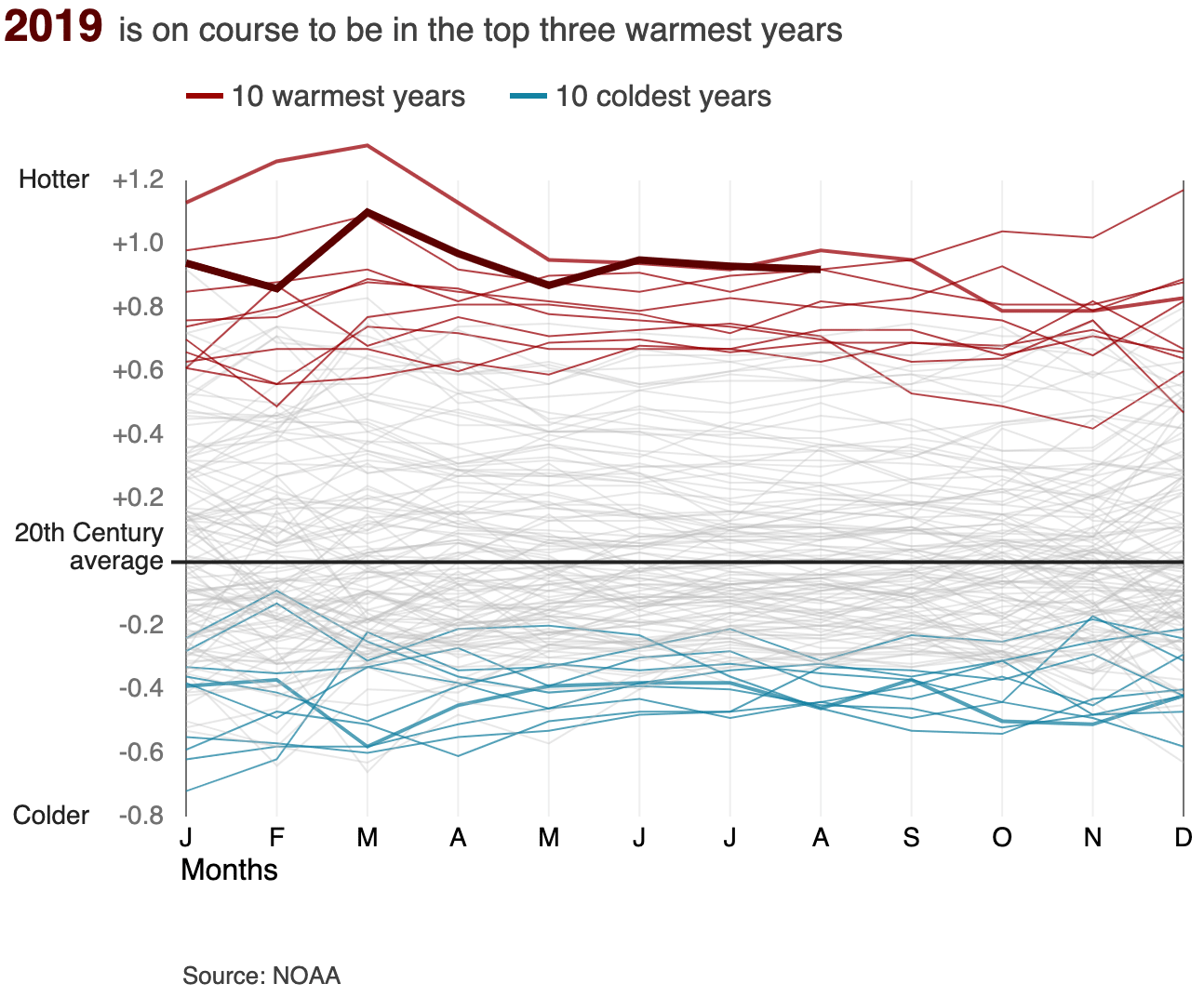

How years compare with the 20th Century average

How years compare with the 20th Century average

Just last year, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned that allowing temperatures to rise more than 1.5 degrees this century would have hugely damaging effects for human, plant and animal life across the planet.

This report says that to keep this target alive, the world needs to cut emissions by 7.6% every year for the next 10 years.

“Our collective failure to act early and hard on climate change means we now must deliver deep cuts to emissions – over 7% each year, if we break it down evenly over the next decade,” said Inger Andersen, Unep’s executive director.

The report pays particular attention to the actions of the richest countries. The group of the 20 wealthiest (G20) are responsible for 78% of all emissions. But so far, only the EU, the UK, Italy and France have committed to long-term net zero targets.

Seven G20 members need to take more action to achieve their current promises. These include Australia, Brazil, Canada, Japan, the Republic of Korea, South Africa and the US.

For example, Brazil’s plans were recently revised, “reflecting the recent trend towards increased deforestation”.

Three countries – India, Russia and Turkey – are all on track to over-achieve their plans by 15% but the authors of the report say this is because the targets they set themselves were too low in the first place.

For three others – Argentina, Saudi Arabia and Indonesia – the researchers are uncertain as to whether they are meeting their targets or not.

That leaves China, the EU and Mexico as three countries or regions that are set to meet their promises or nationally determined contributions (NDCs), as they are called, with their current policies.

Without serious upgrades to most countries’ plans, the UN says the 1.5C target will be missed by a significant amount.

“We need quick wins to reduce emissions as much as possible in 2020, then stronger NDCs to kick-start the major transformations of economies and societies,” says Inger Anderson.

“We need to catch up on the years in which we procrastinated,” she added. “If we don’t do this, the 1.5C goal will be out of reach before 2030.”

The report outlines some specific actions for different countries in the G20.

So for Argentina it’s recommended that they work harder to shift the public towards widespread use of public transport in big cities. China is urged to ban all new coal-fired power plants, something that recent research casts doubt on.

The biggest focus of action is the energy system. To get a sense of the massive scale of change that is needed, the study says the world will have to spend up to $3.8 trillion per year, every year between 2020 and 2050 to achieve the 1.5C target.

The impression that time is running short is reinforced by the report – and UN negotiators gearing up to meet in Madrid next week at COP25 are feeling the pressure to increase their ambitions on carbon.

“This is a new and stark reminder by the Unep that we cannot delay climate action any longer,” said Teresa Ribera, Spain’s minister for the ecological transition.

“We need it at every level, by every national and subnational government, and by the rest of the economic and civil society actors. We urgently need to align with the Paris Agreement objectives and elevate climate ambition.

“It would be incomprehensible if countries who are committed to the United Nations system and multilateralism did not acknowledge that part of this commitment requires further climate action. Otherwise, there will only be more suffering, pain, and injustice.”