Climate at COP28 in Dubai

We are about to pass a civilisational milestone, say forecasters.

In the next few years we will pass ‘peak’ fossil fuels – it may have already happened.

It will mean the world has reached its maximum use of coal, oil and gas and demand will begin to decline.

It is an incredible achievement and something we should be celebrating far more enthusiastically, but it also raises crucial questions.

Will the transition to a new clean energy system happen quickly, or will we fry the planet first?

That’s what the huge UN climate conference in Dubai is really about.

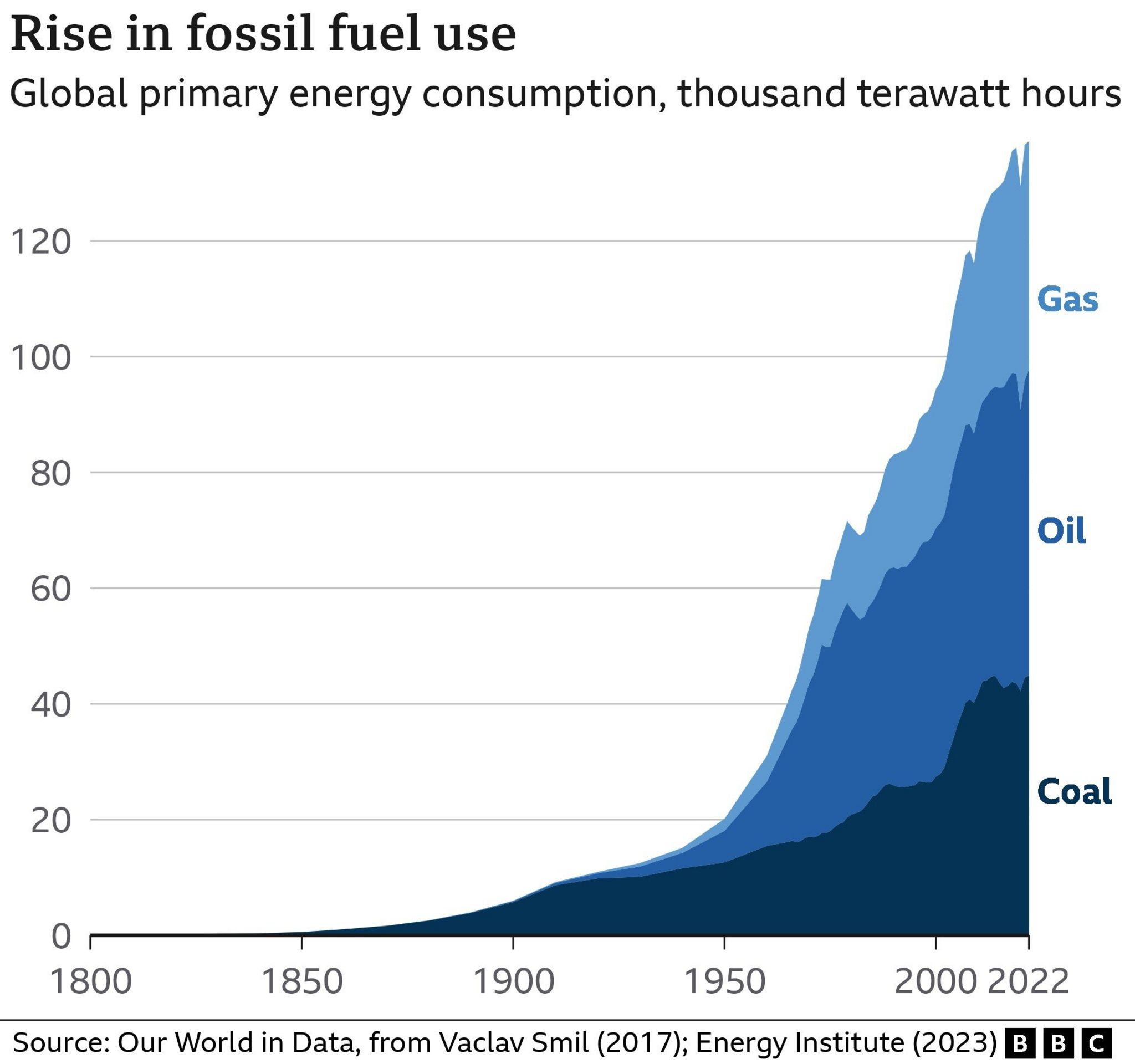

And, we may be reaching the peak, but the fossil fuel mountain is much higher than most of us realise.

The International Energy Agency (IEA), a respected world authority on the subject, predicts global fossil fuel use will peak in 2025, even if governments don’t introduce any new climate policies. IEA Executive Director Fatih Birol called this an “historic turning point”.

What kind of a challenge do we face?

The legendary academic and expert on the role of energy in human society Vaclav Smil, explained to me once that energy isn’t just another input in the global economy, like steel, innovation or information technology – it IS the economy.

“The economy is basically converting one form of energy into another, that’s all it is, right? Without having energy, there is no economy,” he told me.

He’s deeply sceptical about how easily we’ll wean ourselves off the fuels that are warming the planet.

“We are a fossil fuel society, I’m sorry about this,” he said, emphasising that we’re talking about a billion tonnes of steel a year, four billion tons of cement, and four billion tons of liquid fuels. These astronomical numbers are almost beyond our comprehension.

That reflects just how central energy is to absolutely everything we do.

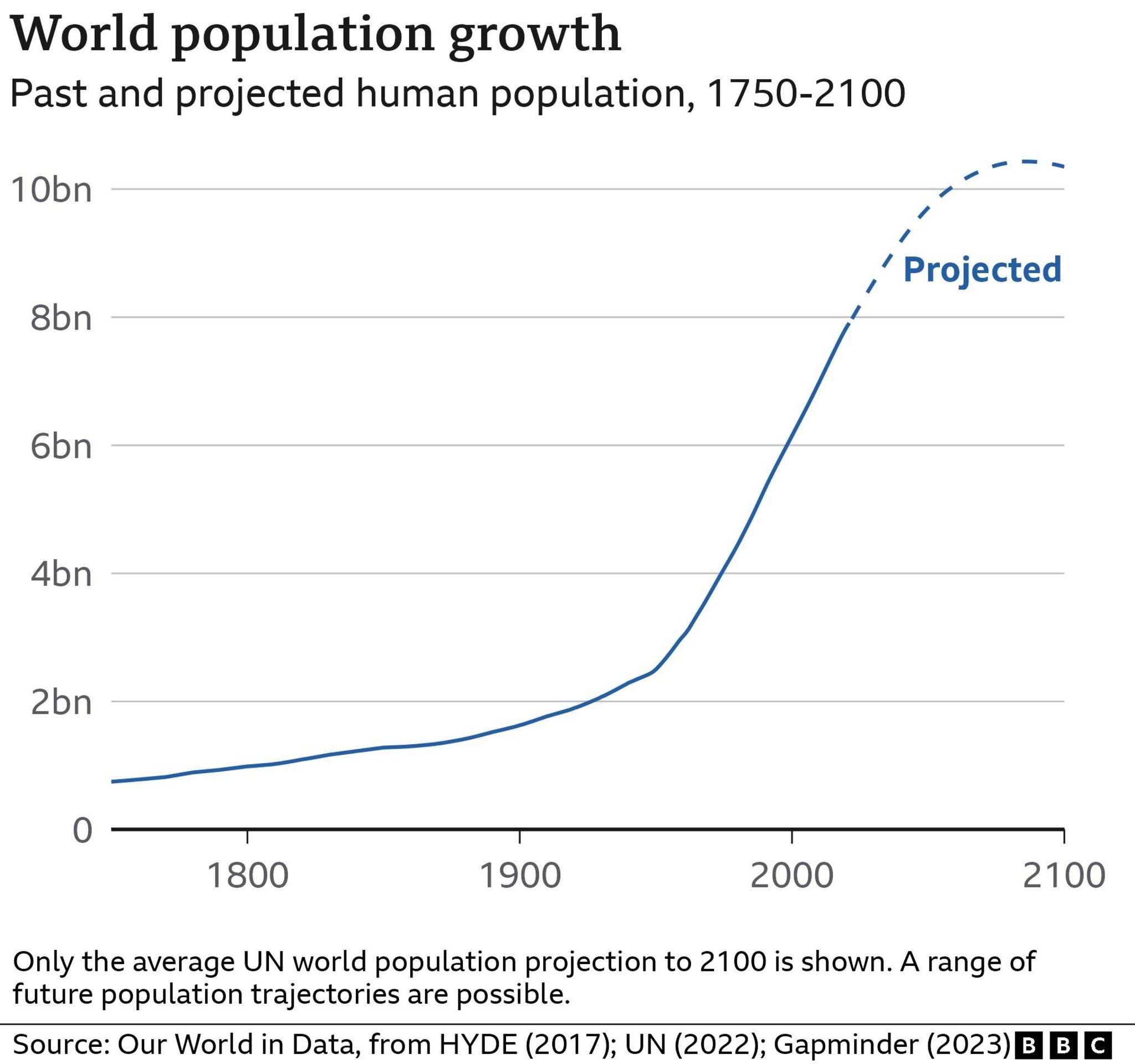

Our species has been around for about 300,000 years.

For 299,000 of those years virtually all of us lived short lives marked overwhelmingly by drudgery and poverty.

That all began to change about 1800 when we began to exploit the world’s vast stores of fossilised sunlight.

The switch to coal, oil and gas sparked the industrial revolution and with it explosive economic growth.

Horses gave way to the steam engine, then the internal combustion engine, then the jet engine.

And all the while the human population grew: from a couple of million of us at the end of the ice age, to a billion at the dawn of the industrial revolution and now more than eight billion human beings.

But the unprecedented productivity of the industrial world means most of us enjoy prosperity and health even our grandparents would find astonishing.

Our hunting and gathering ancestors got by on about 10 gigajoules of energy a year. The average American uses 50 times that now, Prof Smil estimates.

In short, the energy mountain we have climbed is truly gargantuan.

And we may be nearing the peak of our fossil fuel use, but 80% of the energy we use still comes from them.

That is the challenge for the next energy revolution, the one the world is discussing at COP28 in Dubai – the switch to renewable energy.

So, how’s that coming along?

Wind and solar – the two great hopes for our clean energy future – have been growing rapidly.

They accounted for around 12% of electricity generation in 2022, according to IEA figures, up from virtually nothing just a few decades ago.

But most electricity – 70% of the total – is still generated from coal, oil and gas.

And electricity accounts for just one fifth of the world’s total energy consumption.

So wind and solar are actually only responsible for around 2% of global energy supply.

The reason we are reaching the peak of the fossil fuel mountain has less to do with renewables than it has with the growing efficiency of the world’s power stations, steel works, cement kilns, fertiliser plants, glass factories, ships, planes and cars.

So, can we learn to do without them?

Chris Stark, the head of the UK’s climate watchdog, the Climate Change Committee, is more upbeat than Prof Smil.

He pointed out to me here at COP28 that moving away from fossil fuels will involve electrifying virtually everything, and electric devices tend to be more efficient than those powered by fossil fuels.

“Think of the heat that comes off the bonnet of your car,” he says. “It is wasted energy. You don’t get that with an EV.”

Similarly, for every unit of energy you put into a gas boiler you get one unit of heat out. For an electric-powered heat pump you get three.

Stark’s point is that by switching to the electric solution you are reducing energy demand – making the mountain smaller. “Demand destruction” he calls it.

Renewable electricity is now often cheaper than fossil fuels so the switchover will save us all money over time, Mr Stark points out – and we all like to save money.

We don’t need big government subsidies to make it happen, he says, private cash should do the heavy lifting on this.

But with renewables the big costs are upfront, when you install the solar panels or wind turbines.

The savings come because the fuel – sun and wind – are free.

Those upfront costs are an issue for poorer countries, which struggle to afford expensive projects.

But there is progress on that too, thanks in large part to the efforts of the prime minister of tiny Barbados, Mia Mottley.

An investor raising money for a solar farm in Germany pays four or five per cent a year on a loan, in Zambia it is more like 20%, her team says.

Ms Mottley thinks she has ways to drive those interest rates down, and now has the backing of the new head of the World Bank, the Washington-based institution which helps developing countries advance their economies.

If it can absorb some of the risk of putting money into renewables in developing countries, that could release hundreds of billions of dollars in loans from banks and other commercial organisations, Ms Mottley believes.

So we are moving forward. The International Energy Agency is predicting the share of fossil fuels in global energy supply – stuck for decades at around 80% – will decline to 73% by 2030.

“The transition to clean energy is happening worldwide and it’s unstoppable. It’s not a question of “if”, it’s just a matter of “how soon” — and the sooner the better for all of us,” says IEA Executive Director Fatih Birol.

But remember how big the mountain is. We need to electrify everything for everyone on the planet and we need to do it pretty much all at once – the science tells us we’ve only got a couple of decades.

So, if you are wondering why we have reached the 28th of these COP conferences and we still haven’t solved the climate problem, there’s your answer.

By Justin Rowlatt